This Could Be the Start of Something New

Between the thrill of novelty and the pleasure of mastery, learning—how to speak French, dance flamenco, build a sandcastle, anything—makes your heart pick up a beat and your world expand. Where to begin? Right here—with true stories of skills attained and new territory conquered.

BY MICHELLE BURFORD | O, THE OPRAH MAGAZINE | JUNE 2008

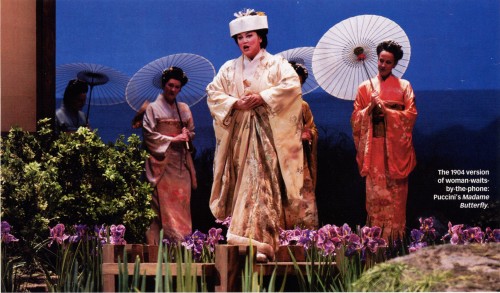

Neuroscientists say you can change your brain’s shape by trying a new activity—like attending the opera, which I did for the first time in 2003. Above, the 1904 version of woman waits by the phone: Puccini’s Madame Butterfly.

Five years ago, I made a list—the 150 teensy and gigantic things I plan to do while I’m alive. Year by year—or semester by semester, as I see it—I cross one activity off the list and replace it with a new one. Learn to backstroke a quarter of a mile. Done. Salsa dance in an Amsterdam pub at midnight. Exhilarating. Take a trapeze lesson (closest thing to flying), host a red-dress disco party (I’m still recovering), take up tap dancing (rhythm is a must). This semester: opera tickets and a trip to Korea.

I’m an opera virgin. When my housemate, Julia—a Korean-American investment banker and opera connoisseur—heard that, she flipped. Pronto, we bought tickets to New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Before sniffling though Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly (the tragic 1904 version of woman-waits-by-the-phone) we stopped in Manhattan’s Koreatown for a bowl of jap chae (glass noodles with vegetables). That’s when I resolved to knock out items 38 and 96 on my list: To master the intricacies of opera and sample ten foods in Korean cuisine. This August, armed with dozens of words in Julia’s native language, I’ll board a flight to Asia with my buddy.

Neuroscientist Michael Merzenich says that at around age 30, your memory and cognitive abilities begin to decline, but when you learn a new skill, you keep your brain in shape.

“The best thing for being sad is to learn something,” said the wizard Merlin to young King Arthur in T.H. White’s novel The Once and Future King. “That is the only thing that never fails.” Turns out this view has scientific underpinnings. The brain is evolutionarily primed to seek and respond to what is novel, says Lawrence C. Katz, PhD, a professor of neurobiology at Duke University Medical Center in North Carolina and the coauthor of Keep Your Brain Alive. He says you can improve your recall by practicing a daily session of what he calls neurobics.

Oh, exhale: This doesn’t involve weights, sweaty towels, or treadmills. According to Katz, any major break from the ordinary—brushing your teeth with the opposite hand, for example—stimulates the brain. Michael Merzenich, PhD, chief scientific officer of Neuroscience Solutions, concurs. He says that at around 30, our memory and cognitive and motor abilities begin to decline, but anytime you learn a new skill, you change the brain physically. “Let’s say you learn ‘Chopsticks’ on the piano,” he explains. “If you looked at the brain [after mastering it], you’d see changes in the response of millions of neurons. The brain is a ‘plastic’ instrument that has continuous capacity for change.” To Merzenich, brain fitness is every bit as important as physical fitness.

Writer and radio host Barry Farber knows that. He can speak at least 25 languages, among them French, Danish, and Hebrew. I met Farber because he was teaching a class I attended recently–Build a Million Dollar Vocabulary in Just One Night. Not only do I now know the difference between an encomium and an incumbent, but I can tell you why acquiring knowledge is the first step in stirring up your brain juices. We have enough moments to learn a language every year, Farber says. Harnessing those otherwise meaningless scraps of time, he explains, can turn you into a master of linguistics.

Or a student of every item on a Korean menu. Or a backstroker once terrified of water. Or a rhythmically challenged black woman who shelled out $60 for tap shoes. If T.H. White’s prescription for joy is to learn something new, I intend to seek out as much happiness as my arteries can hold—one opera at a time.

Need a great story on a tight deadline? E-mail me at Michelle@MichelleBurford.com