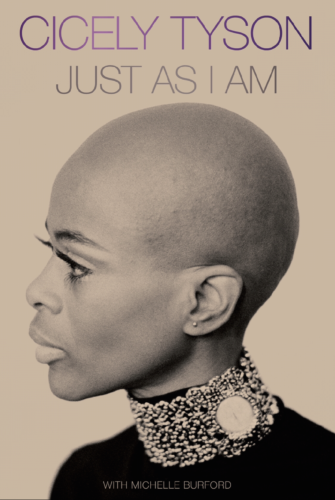

Just As I Am

Just As I Am debuted at #1 on the NYT Best Seller list and remained on the list for ten weeks. The Oscar, Tony and three-time Emmy Award-winning actress shares her extraordinary life story in a book The Oprah Magazine calls an “essential, passionate, raw, revelatory account of a woman who refused to allow any obstacle to thwart her quest for excellence—racism, misogyny, poverty, single motherhood—and today stands as one of the greatest actresses of all time.”

The New York Times says of Michelle’s writing: “The firm, warm, proud, reflective voice on the page, in full keeping with the star’s onscreen image, is the creation of Michelle Burford, a gifted ‘collaborator and story architect,’ as she calls herself…I linger on this ‘with’ credit, because I like to think Tyson herself must admire the enterprise with which Burford has turned her specialized skills into such success…Burford, a sensitive listener, has organized 96 years’ worth of stories with grace. Right about now, the autobiography of Miss Cicely Tyson is a balm for the afflicted.”

BOOK EXCERPT | HARPER COLLINS | JANUARY 2021

Ms. Cicely Tyson passed away on January 28, 2021, two days after the publication of her acclaimed memoir. She lived for ninety-six years—more than 35,000 sunrises.

When Cicely Tyson first began training as an actress, she endured a harrowing Me Too moment that both devastated and emboldened her. The following excerpt is from Chapter 10, entitled “Center Stage”:

It’s not every day you find yourself seated next to Marilyn Monroe. Such a day arrived for me in 1956, not long after I’d devoted myself to acting.

The Spectrum, by then, was an afterthought. Once Warren’s coffers had run dry halfway through filming, he never could replenish them, even once he’d left skid marks all over Manhattan, attempting to raise capital. Rather than simmering in that setback, he linked arms with director Harold Young and screenplay writer Charles Gossett on Carib Gold, a maritime movie about a shrimp boat crew that discovers a sunken treasure. Diana Sands, who’d become a dear sister-friend to me, was cast in the film. So was I, though not as the lead. I was to play Dottie, wife of a deckhand. Perhaps strangely to some, I felt relieved not to play the principal role. With my career still in its infancy, my preparation had yet to catch up with my passion. By the time Warren connected with Harold and Charles about the script, the inimitable Ethel Waters, the Twenties blues singer who, by that time, had begun lending her artistic deftness to the stage, had already been tapped as Carib’s headliner.

“Do you even want to be in the film?” Warren had asked me, having observed my periodic vacillations between euphoria to be in the industry, and murmuring about how ruefully ill-prepared I felt. I shrugged. During one particularly low valley, I’d even threatened to go back to the Red Cross. What stopped me was the stubbornness passed onto me from a certain Fredericka Theodosia Huggins, the woman I was set on rebutting.

“Well what do you want?” Warren pressed, aggravation in his tone.

“I want to learn what it’s all about,” I said, sighing. “I don’t know what I’m doing, Warren. I don’t understand it. I need to study.”

There is no archetype on file in which a black woman is simultaneously resolute and trembling, fierce and frightened, dominant and receding. My mother, a woman who, amid abuse, stuffed hope and a way out into the slit of a mattress, is the very face of fortitude. I am an heir to her remarkable grit.

However, beneath that tough exterior, I’ve also inherited my mother’s tender femininity, that part of her spirit susceptible to bruising. The myth of the Strong Black Woman bears a kernel of truth, but only a half-seed. The other half is delicate and ailing, all the more so because it has been denied sunlight.

Thus began my months-long quest for formal training. Warren persisted in his belief that my innate gifts would be enough to carry me, that the well of emotion stored up during my childhood, formed by my wail amid strife in my family’s eastside home, shaped when I witnessed my mother up for auction on a Bronx sidewalk, was all the training necessary for me to infuse my portrayals with authenticity. It wasn’t. Trauma may give rise to intense feeling, but to refine one’s artistry, an actor must be taught to channel the unbridled rawness of that emotion, to effectively use it in service of a character’s every groan and grimace. Rather than placing me in a course for total beginners, Warren instead sent me to a downtown studio for actors with some experience, albeit limited. The course gave me a migraine. What are these people even talking about? I’d sit in class thinking. How do they know how to gesture, whether to speak, when to emote? I couldn’t grasp it. I don’t remember the instructor’s name, but I do recall becoming friendly with his wife.

“You know,” I told her after class one day, “I really don’t like this.”

“Why not, Cicely?” she asked. “What’s the matter?”

“Because I don’t understand what’s happening,” I said. “I need someone to explain this whole thing to me.”

“Don’t worry,” she said, smiling, “it’ll come.”

It didn’t—even after I’d stayed on for several more classes. She and Warren kept claiming, counterintuitively to me, that I was lost because I had too much skill. “The problem is that you’re so far ahead of your classmates that there’s nothing there for you to learn,” Warren said. That assertion made no sense to me. As far as I could see, I had plenty to learn, whether or not he acknowledged it.

The next experience was significantly better but still no bull’s-eye. Warren connected me with Miriam Goldina, the Russian-born stage actress and drama coach who’d studied under Konstantin Stanislavski, the grandfather of method acting—a technique requiring a performer’s full immersion in the emotional realities of the character to be portrayed. Miriam taught me some tangibles. For one thing, she made me acutely aware of the importance of words: how to listen closely to them, how to read the spaces between them, how to become cognizant of the intent behind each. When you’re in conversation with someone, why might they be saying what they are saying? What is it that he or she is trying to elicit from you? We examined those questions and many others, making me conscious of how critical it is for an artist to do more listening than speaking, a skill I’d been unknowingly practicing since my earliest years. What Miriam and I did not explore was what she likely assumed I already possessed—the fundamentals of acting, theater 101. More than anything during that time, I craved a foundation.

That is exactly what I told Lee Strasberg on the day I enrolled at the Actors Studio, then the most prestigious theatrical collective in the nation. Lee, who’d refined and further developed Stanislavski’s approach to method acting and introduced it to the West, was training greats such as Robert De Niro, Anne Bancroft, and Jane Fonda. Surely he could guide me through my labyrinth of confusion and give me the basics.

“Please,” I begged him, “I don’t want to be put in a class with professionals. I want to start from the beginning.”

Lee nodded as if he agreed, but he apparently took Warren’s word over mine and placed me with the pros. That’s how I ended up an elbow’s length away from the blonde and beguiling Marilyn Monroe, then fresh off her run in the blockbuster romantic comedy The Seven Year Itch. I, too, had an itch, an instinct to flee the second I spotted her: Lord in heaven, what am I doing here!? “Hello,” she purred in my direction. That was my first time in class with Marilyn. It was also my last.

I huffed my way out of there and over to Warren’s office. “When I tell you I want to start at the bottom,” I said, “I mean the very bottom, not in a class with a big star!”

Warren, as amused by my tantrums as he was accustomed to them, just laughed. “Well all right, Cicely,” he said. “Maybe it’s time I send you over to Lloyd Richards.”

I knew the name. Diana had mentioned the distinguished acting coach to me on several occasions, most notably when I’d fallen into one of my steepest stupors about my inexperience. I’d uttered another (empty) threat that evening: I was one melancholic episode away from returning to my day job.

“You know, you really should go down to Paul Mann Actor’s Workshop,” Diana told me. “Lloyd Richards, Paul’s business partner there, is supposed to be one of the best. Try it. And if, after you go, you find that you still can’t make sense of this business, then you can quit. But please give yourself a chance.”

Paul, an accomplished theater actor who’d founded the workshop in 1953, was Caucasian. Lloyd—a renowned African-American actor and director who, years later, went on to serve as dean of the Yale School of Drama—had created a nurturing environment for black artists. Sidney Poitier had studied with Lloyd. So had Harry Belafonte, Ruby Dee, and Billy Dee Williams. That was résumé enough to get me across the threshold to the school.

My initial appointment was with Paul, whose introductory course was required for incoming students. Our meeting began as such encounters do, with handshakes and smiles and niceties. It ended traumatically.

“So Cicely,” he said after we’d been chatting for a few moments, “where do you see yourself going in this industry?”

As I thought about his questions, his gaze traveled down from my eyes to my chest. My heartbeat raced. Paul rose from his desk and walked over to shut his door. I stood, as did every hair on my neck.

“Well, I mean,” I stammered. Before I could continue, Paul, a menacing tower of flesh, thrust himself toward me and began manhandling my breasts, attempting to remove my blouse as I shoved him away. “No!” I yelled. “Get off of me!” He tried to jam me against the wall and shove his hand under my camisole, but I somehow managed to break free. Once I’d pried myself loose, blouse untucked from my skirt, hair scattered in every direction, I grabbed my pocketbook and fled to the door. As I reached for the knob, Paul spoke. “Class begins next week,” he said in an eerily calm voice, as if he hadn’t just attacked me. “You are welcome to come.” Without looking at him, I opened the door and disappeared down the hall, holding back tears long enough to make it out the front door. Once home, I collapsed into sobs on my bed.

A week later at the start of his course, I showed up. Paul had already gathered with the group of students who’d enrolled in his introductory class, and when I entered, he ceased speaking and stared in my direction. “I thought I’d never see you again,” he said, incredulousness in his tone. I breathed not a sentence and took a seat.

Life is choices, and as I saw it, I had two. I could’ve fled from that man’s office and never returned. Many, understandably, might have chosen that route. And yet the alternative option, the less obvious of the two, was the one I settled upon. I’d arrived at that studio with the singular purpose of potentially training with Lloyd. And though Paul, in a show of brash lasciviousness, had attempted to thwart my mission, I was not to be deterred. When someone sees you headed in a particular direction, and he or she throws a brick into the road, that is the precise moment to forge onward, with greater velocity, toward your destination. I had a purpose, one that, despite all of my wavering, I had witnessed God orchestrating. And I refused to have some man, with his hot breath on my neck and his pasty fingers on my nipples, impede my plan.

It was never Paul’s name that had been spoken to me. It was Lloyd’s. And whatever it was that Lloyd had to offer me, I intended to get it. If that meant enduring Paul’s course so I could move onto Lloyd’s permanent tutelage, so be it. If that involved swallowing the recollection of his brazen assault, of forgetting what he’d stolen from me in the same manner a passerby once had—if that was the price to be rendered, I stood ready to pay. What Paul did to me that day, the way he put his hands on me—the trauma, all these years later, is emblazoned on my memory. When someone violates you sexually, it does not simply haunt and aggrieve you. It alters the very shape of your soul.

And altered I was. Contrary to the mythology surrounding the unflinching nature of African-American women, we, too, experience trauma. Black women—our essence, our emotional intricacies, the indignities we carry in our bones—are the most deeply misunderstood human beings in history. Those who know nothing about us have had the audacity to try and introduce us to ourselves, in the unsteady strokes of caricature, on stages, in books, and through their distorted reflections of us. The resulting Fun House image, a haphazard depiction sketched beneath the dim light of ignorance, allows ample room for our strength, our rage and tenacity, to stand at center stage. When we express anger, the audience of the world applauds. That expression aligns with their portrait of us. As long as we play our various designated roles—as court jesters and as comic relief, as Aunt Jemimas and as Jezebels, as maids whisking apéritifs into drawing rooms, as shuckin’ and jivin’ half-wits serving up levity—we are worthy of recognition in their meta-narrative. We are obedient Negroes. We are dutiful and thus affirmable.

But when we dare tiptoe outside the lines of those typecasts, when we put our full humanity on display, when we threaten the social constructs that keep others in comfortable superiority, we are often dismissed. There is no archetype on file in which a black woman is simultaneously resolute and trembling, fierce and frightened, dominant and receding. My mother, a woman who, amid abuse, stuffed hope and a way out into the slit of a mattress, is the very face of fortitude. I am an heir to her remarkable grit. However, beneath that tough exterior, I’ve also inherited my mother’s tender femininity, that part of her spirit susceptible to bruising and bleeding, the doleful Dosha who sat by the window shelling peanuts, pondering how to carry on. The myth of the Strong Black Woman bears a kernel of truth, but only a half-seed. The other half is delicate and ailing, all the more so because it has been denied sunlight. On the day I went back to Paul’s school, I was unswerving in my resolve to study with Lloyd. I was also vulnerable—as traumatized by Paul’s behavior as any woman might have been.

I knew Ruby Dee and Sidney Poitier not as the theatrical giants the world would come to regard them as. I knew them as human beings, first and foremost, grappling with their private insecurities and frights, struggling to breathe air into their characters’ lungs. I knew them as waitresses and as dishwashers, as clerks and as survivors, as dreamers moonlighting their way to some semblance of solvency.

My decision to return became a defining one, a choice that sent a resounding echo through the decades of my career. After I’d endured Paul’s course, eyes averted, nose in my notebook, I went on to train exclusively with Lloyd, one of two genius coaches who molded me in those years. I managed to completely avoid Paul, only showing up at the studio when Lloyd was teaching. By the time Lloyd and I connected, I’d begun work on Carib, flitting between New York and Key West, Florida, where the movie was shot. When I returned to the city during breaks in filming, I couldn’t get over to Lloyd’s office fast enough, ready to soak in all he had to teach me—about exploring my character’s emotional truth, about enhancing my understanding of her given circumstances, about making artistic choices commensurate with that awareness.

At the school, I got to know Ruby Dee. She was also in training then, though alongside my shade of bright green, Ruby and her husband, Ossie Davis, were already deep-emerald sages of the stage. Ruby, diminutive yet spirited, was as much a firecracker then as her decades of civil rights crusading, in front of the curtain and beyond it, would reveal her to be. “Girl, I’ll tell you,” she’d often say to me then, “if you can be black and live in this world, you can be anything you want to be.” Ruby, who by 1956 was nearly two dozen stage and film credits into her career, had experienced the humiliations that just come with Acting While Black, of having nearly every available role be that of a domestic, of loaning her talents to directors who, away from the lights, sneered down at her as genetically and intellectually subpar.

Ruby had cut her thespian teeth amid such insults. She, Ossie, Harry, Sidney, Isabel Sanford, Alice Childress, Hilda Simms, and scores of other then-unknown artists had come up through the American Negro Theater, a 1940s community theater group founded by black actors, in part as a response to the dearth of roles illuminating the breadth of our experience, and in part to create a warm cocoon for black actors confronting bigotry in the shadows of The Great White Way. In the group’s early years, actors rehearsed in the basement of the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library and performed at Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Ruby and the rest of them understood that the most difficult part of our work happened not in studios and rehearsal spaces, not on stages and sets. Just walking through this world as a black person, and actually surviving that, was and still is an ovation-worthy performance.

During those times, I knew Ruby and the others not as the theatrical giants the world would come to regard them as. I knew them as human beings, first and foremost, grappling with their private insecurities and frights, struggling to breathe air into their characters’ lungs. I knew them as waitresses and as dishwashers, as clerks and as survivors, as dreamers moonlighting their way to some semblance of solvency. The introverted Sidney, who began work on A Raisin in the Sun in the late 1950s, was always more confident on film than he was before a live audience, when nerves, at times, got the better of him. Such tremors had arisen during Sidney’s 1946 Broadway debut in Lysistrata, when his pre-show peek at a packed house sent his teeth to chattering. When he walked out on stage, he forgot his first line and skipped straight to his eighth. And still, his talent shone through. The show was critically panned, yet Sidney received favorable reviews, enough of them to untie his tongue and put fresh wind at his back.

It was Sidney who connected Lloyd and Lorraine Hansberry—the soft-spoken revolutionary who penned Raisin as a head-nod to Langston Hughes’ poem, and in memory of her own childhood marred by flagrant prejudice. Sidney had a longstanding pact with his friend and director. While a student at Paul Mann Actor’s Workshop, Sidney once said to Lloyd, “If I ever do anything on Broadway, I want you to direct it.” So when Lorraine’s scintillating script landed in his possession, he knew exactly where to take it. In Lloyd’s gifted and nimble hands, and with the prowess of an all-black cast headlined by Sidney as Walter Lee Younger and Ruby Dee as his wife, Ruth, the play lit Broadway ablaze, even as it re-ordered theater’s playbook. Before Raisin, the prevailing wisdom among the industry’s power brokers was that white audiences would support an all-black show only if it were a musical, with us shimmying and guffawing our way toward an enduring stereotype. The rapturous applause and repeated curtain calls, with a verklempt Lorraine urged by the roar to take her bow of validation, demonstrated otherwise. “Never before,” James Baldwin commented of the play, “had so much of the truth of black people’s lives been seen on stage.” And it was Lloyd, God rest his soul, who had, in one way or another, molded every performer in that trailblazing production.

For months before I connected with Lloyd, Warren would often ask me, “What are you looking for in a teacher?” I never quite knew how to answer. Once Lloyd and I began training together, I realized I’d been looking for a rock, which Lloyd provided. His method acting approach was not substantively different from what I’d become familiar with up to then. But his manner of delivery, the patience with which he illuminated the tenets, the haven he created for actors—he became the Gibraltar that I and countless others stood upon.

Stylistically, Lloyd was more co-pilot than captain, more laissez-faire than commander, a teacher who preferred his student to fly solo as he, reservedly in the wings, whispered cues during the route. He was less apt to deliver a sermon, more likely to raise a thoughtful question. “Who is she?” Lloyd would ask me about a character I was preparing to depict. “What are the moments that have shaped her?” He understood that meeting a character on the page was akin to making her acquaintance in life. To study that character—to insatiably pursue her backstory, to dissect her memories and her motivations—was to begin the process of becoming her. That is why, to this day, I read a script a hundred times over, steeping myself in the nuances of the character, searching for the silence between the notes in the melody of who she is. By the time I get on that stage, I’ve lived in my character’s skin so continuously that she often takes over my physical being. Where did that come from? I think when a gesture, a head tilt, or a smirk distinct from my own emerges. Lloyd laid the foundation for that to happen. These days when I talk to young people aspiring to the stage, I tell them, “You can spend half your life trying to find the right teacher for you.” Lloyd and I were simpatico from moment one.

Had I allowed Paul to short-circuit my dream, I might have missed out on the blessing of Lloyd, whose artistic skill was eclipsed only by his kindness. In contrast to his business partner, he was, for me, a torchlight of integrity. In 1984, decades after my experience with Paul Mann, eight actresses accused him of sexual assault. In a civil suit that landed in the New York State Supreme Court, the scales of justice leaned in the direction of the women. Paul was issued a guilty verdict and ordered to pay his victims $12,000 in total, a paltry $1,500 for each of them. Before his death in 1985, Paul had given much of his life to the theater, training artists and accruing accolades. History has recorded him as a celebrated teacher, one who prepared numerous luminaries for the stage. Yet in my book, he will forever be regarded as the man who, along my path toward Providence, hurled a brick—one I picked up and threw back at him.