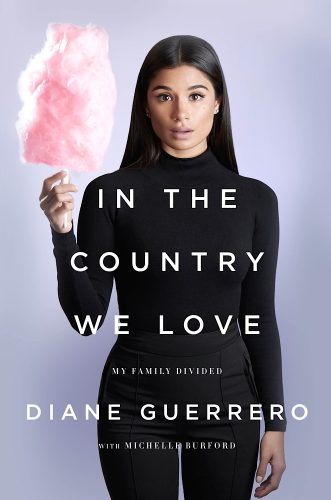

In the Country

We Love

Diane Guerrero, co-star of the hit Netflix series Orange Is the New Black, grew up fearing that her mom and dad, undocumented workers from Colombia, would be deported. One afternoon in spring 2001, that fear came true. All at once, Diane, then just 14 and a U.S. citizen by birthright, was abandoned. No government official or child services worker ever checked up on her. Relying on the kindness of friends, Diane stayed in America, finished school, and built a successful acting career—all while enduring the agony of her family’s separation.

BOOK EXCERPT | HENRY HOLT & CO. | MAY 2016

When Diane was a freshman at Boston Arts Academy, she came home to discover that her parents had been taken by immigration officers. Each was sent to a detention center to await deportation. In the chapter entitled “Left Behind,” Diane sees her mom through a plastic partition for the first time.

I will always remember that prison waiting room: Hot. Crowded. Musty. Several rows of attached metal chairs, the kind you see in airports, lined the cement walls. On my row, a teenage mother tried to calm down her screaming baby; two seats over from her, an old man dozed off with his cane at his side. No one spoke. Anna leaned toward me.

“You ready, hon?” she asked.

I shrugged. “I guess,” I said, although I knew that wasn’t true. Are you ever actually ready to see your own mom locked up? I don’t think so, and definitely not when you may never see her again. But I couldn’t say that out loud. Not to the one person who’d been willing to take me in.

The summer I lost my parents, it was the strangest kind of heartache. No friends gathered to grieve over the departed. No flowers were sent. No memorial service was planned. And yet the two people I’d cherished most were gone. Not gone from the world itself, but gone from me. We’d find a way to carry on. Just not with the promise of each other’s presence.

I’d been to a prison when I was small. A few times, my mother took me to an immigration detention center so we could see some neighbors of ours who were fighting deportation. “We need to go and lift their spirits,” Mami told me as she fastened the back buttons on my pink cotton dress. “They need us right now.” This is going to sound nuts, but I actually looked forward to going. The guards were so nice to me. My mother, who knew how much I loved sweets, bought me a big chocolate-chip cookie from the vending machine. At age six, the whole experience felt like a fun field trip. At fourteen, it was the most terrifying day I’d ever faced.

The guard, a tall black man with dreads, lumbered into the doorway. “Ladies and gentleman,” he announced in a Jamaican accent, “sign in and line up here.” He held up a clipboard and nodded toward the entrance to a metal detector. The room stirred as the fifty or so people gathered their belongings. “Your bags will be thoroughly searched,” he said. “No cell phones are permitted in the visitation area with the detainees.”

The detainees. His words hung there, thick and heavy, in the humid July air. Just weeks earlier, my Mami had simply been my Mami. The loving mother who combed my long, black hair into a ponytail. The mom who made sure I brushed my teeth and finished my homework. Then on an afternoon I’ve spent a decade wishing I could undo, Mami had been suddenly labeled an inmate. A prisoner. A “detainee.” After spending two months in the New Hampshire facility where I’d already visited her twice, she’d been moved to this jail in Boston. And in less than one hour, she’d be forced out of the country.

“Take off all of your jewelry,” instructed the guard, “and remove any coins from your pockets.” I swiped my fingers through the two back pockets of my jean shorts. Empty. I reached up to unfasten my gold necklace, the one my parents had given me for my tenth birthday. I lowered the chain into the guard’s plastic bowl and stepped through the detector. Anna followed.

We made our way down a hall and into a second waiting area, more depressing than the first. The guard rounded the corner into the room. He was holding the clipboard. “When you hear your name,” he barked, “please stand and follow me.” I held my breath as he read off the first name. Then the second. Then the third and fourth. Ten names in, I heard what I’d been listening for but dreading: “Diane Guerrero,” he announced. Anna and I took our places among the others.

The group filed out behind the guard. Halfway down the hall, he stopped in front of a steel door. Above it hung a sign: “Inmate Visitation Area.” With the full weight of his right shoulder, the guard leaned into the door and swung it open. He motioned for us to walk through.

The room reeked of bleach. Under fluorescent lights, about twenty inmates sat lined up in booths. Each of them was on a stool behind a giant plastic barrier. Every booth had one of those old-school phones in its upper left-hand corner. Five or six guards milled around, just watching. As the other visitors scattered to find the prisoners they’d come to see, I stood there and scanned the row, one booth at a time. There, in the middle, I saw Mami. I walked slowly across the linoleum and slid into the chair facing her. Anna reached up and handed me the phone.

I studied my mother’s face. In the eight weeks since her arrest, she’d aged twenty years. She seemed tired and frail, like she hadn’t slept for days. I’d never seen her so skinny. Her eyes were red, her skin pale. Her hair lay haphazardly on the shoulders of her orange jumpsuit. Her wrists were handcuffed together and resting in her lap. A guard on her side of the barrier placed the phone in her hands. She lifted it to her ear and held it there for a long moment.

“Hello, my princess,” she said. Her voice was so soft and feeble that I almost couldn’t hear her. “How are you?”

My fingers trembled as I stared at her through the scratched plastic. I’d promised myself that I wouldn’t get choked up—that I’d hold it together for my mom’s sake. But I could already feel the water building up.

“I’m okay,” I said. I bit down on my lip to keep the tears from escaping. It didn’t work. “I’m, uh—I’m fine,” I stammered.

Mami dropped her head. “Don’t cry, baby,” she said, her own eyes brimming with water. “Please don’t cry.”

With all of my heart, I wanted to reverse time. Rewind the months. Go back to those days, warm and innocent, when I felt safe. When the smell of Mami’s freshly cooked plantains greeted me at our front door. When the sound of Papi’s laughter made me feel like the most precious little girl in the world. When everything still made sense. But I couldn’t go back.

All around the room, different energies collided. To my right, an Indian woman laughed hysterically; to my left, the elderly man who’d been asleep in the waiting room now shouted obscenities. I inched closer to the barrier so I could concentrate.

“I’m really sorry about this whole thing,” my mom said. “I’m so sorry, Diane.”

She didn’t mean for her words to sting, but they did. She was sorry. My dad was sorry. The whole world was sorry. But none of it changed my situation. None of it altered the fact that, by dusk, my childhood would be over.

My mother sniffled. “Did you bring the suitcase?” she asked.

I nodded. At the prison’s entrance, Anna had already given the bag to the guards.

My mother looked intently at me. “What are you going to do, Diane?”

It was an odd question for a mother to ask her own young daughter—and yet it was the one question I’d been preparing to answer since I was a small child. My parents had always had one set of realities; as their citizen daughter, I’d had a very different set. We’d lived with the daily worry that we’d eventually have to separate. Our fear was at last coming true.

I sat forward in my chair. “I’m staying, Mami,” I said. “I’ve gotta stay.”

I’d somehow always known I’d remain. What would I do in Colombia, a place I’d never even been to? What kind of life could I have in a nation so poor that my parents had risked everything to escape? Besides that, things were looking good for me for the first time in years. So as far as I was concerned, I didn’t have a choice. I needed to stay.

“You see that guy?” my mother asked. She tilted her head toward a Dominican-looking guard on my side of the plastic. He must’ve felt us staring, because he looked over at us. “He’s a nice guy,” she said. I wasn’t surprised she’d made friends with a guard; my mother has always been social like that.

“You know what he told me?” she asked.

“What?” I said.

She moved the receiver as close to her mouth as she could. “He said immigration only goes after people if they get a tip.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean they’re not going around looking for random janitors,” she told me. “Someone had to inform them about us.”

I gazed at her. “But who would’ve done that?”

“I don’t know for sure,” she told me. She inhaled, and then slowly released the breath. “That’s why you’ve gotta watch your back,” she said. “Be very careful, Diane.”

I started to cry—and this time, I didn’t hold back. Enormous tears rolled down my cheeks and dripped from my chin. I pulled up the edge of my T-shirt and tried to wipe my face. Anna, who’d been standing beside me the whole time, began rubbing my back. The Dominican guard walked in our direction.

“Are you her daughter?” he asked me. I nodded my head yes. “It’s okay, sweetheart,” he said. “We’re not going to hurt your mom.”For some reason, that made me cry even louder. “So why does she have to wear those handcuffs?!” I shouted. I could feel myself getting hyped. “Can’t you take them off? She’s not going to do anything!” Several people looked over at me.

“I’m sorry, but she has to have those on,” he told me. “That’s the rules.”

Soon after, a guard on my mother’s side yelled, “Wrap it up! Five minutes!” Mami scooted to the edge of her stool, cradling the receiver between her neck and shoulder. She put her face right up to the barrier.

“I love you, honey,” she whispered. She paused, stared down at the floor, and then looked back at me. “Never forget that. I’m so proud of you. Be a good girl, okay?”

I let go of the receiver and cupped my hands over my eyes. There were so many things I needed to tell her, so many words I’d stored away. I wanted to stand up and scream, “My mother is not a criminal! Don’t you people understand? You’ve got the wrong family! Please—let her go!” But as the phone dangled by its cord, all I could do was wail. “Bye, Mami,” I said between sobs. “Goodbye.”

Our time was up. When the guard with the dreads gave the last call, the Indian woman pressed her palms against the plastic, like she was trying to touch the person on the other side. The old man stumbled to his feet, using his cane as leverage.

“You ready, dear?” Anna asked. I stood and pivoted, so I could avoid Mami’s face. As much as I’d longed to see her, I also didn’t want to remember her like this. Not with her wrists chained up. Not in an orange jumpsuit. The person behind that barrier wasn’t my mother. She was a stranger to me.

With hardly a sound, the group shuffled back down the corridor. Anna held my hand while we walked. “This isn’t the end for you, Diane,” she tried to reassure me. But it felt like the end. As devastated as I was for my mom, I was even more scared for myself. She and my dad were going home to family. I was stepping into a future I’d prayed would never come.

Outside, Anna peered out over the lot, trying to recall where she’d parked her Camry. A few hundred feet away from us, near the prison’s side entrance, a white police van pulled up. Anna and I exchanged a look. Seconds later, two guards herded some inmates out onto the curb. My mother was among them.

Just as my mother was stepping into the paddy wagon, she turned and caught a glimpse of me. She froze. I could tell she wanted to say something, to run to me. But before she could make a move, a guard rushed her into the van. “Let’s go!” he snapped.

The engine rumbled on. From her seat in the rear, Mami twisted herself around so she could see me through the bars on the windows. She was trying to tell me something, but I couldn’t figure out what it was. Then all at once, I understood. “I love you,” she was mouthing. “I love you. I love you. I love you.” She repeated the three words until the van turned from the lot and disappeared. I melted into Anna’s arms and bawled.

The summer I lost my parents, it was the strangest kind of heartache. No friends gathered to grieve over the departed. No flowers were sent. No memorial service was planned. And yet the two people I’d cherished most were gone. Not gone from the world itself, but gone from me. We’d find a way to move forward, to carry on. Just not with the promise of each other’s presence.

With all of my heart, I wanted to reverse time. Rewind the months. Go back to those days, warm and innocent, when I felt safe. When the smell of Mami’s freshly cooked rice and plantains greeted me at our front door. When the sound of Papi’s laughter made me feel like the most precious little girl in the world. When everything still made sense. But I couldn’t go back. The only way out was ahead.

Anna spotted her car in the lot. On the drive to her house, I stared from my window in silence. My mother’s warning, the haunting admonition, echoed through me. Be careful. Be careful. Be careful. Tomorrow, I’d begin a new life, one uncertain and frightening. A makeshift family. A different home. A path I’d prayed so hard that I’d never end up taking. I glanced over at Anna, settled back into my seat, and watched the sun descend over the Boston Harbor.

Excerpted from the memoir entitled In the Country We Love: My Family Divided. Published by Henry Holt & Company. Hardcover edition released on May 3, 2016.

Need a bestselling memoir on a tight deadline? E-mail Michelle@MichelleBurford.com