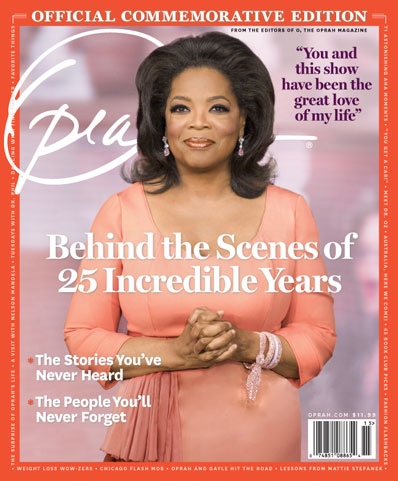

A Few Good Friends

What does it take to get an award-winning talk show off the ground? A whole lot of creativity, a team of the super-committed and an ongoing quest for interesting topics. In this exclusive, Oprah and some of her founding producers look back at the nail-biting days of the big launch.

MICHELLE BURFORD, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

THE OPRAH SHOW COMMEMORATIVE | JUNE 2011

The premiere episode of Oprah’s national talk show aired on September 8, 1986. The topic: “How to Marry the Man or Woman of Your Choice.” From day one, Oprah claimed the top spot in the ratings, even besting talk-show titan Phil Donahue. Oprah’s show held onto that first-place ranking for its entire 25-season run.

My show began with a small team—the band of producers I shared a tiny office with on State Street. Some us had been together since my 1984 premiere on A.M. Chicago, the local WLS program that became The Oprah Winfrey Show. So by the time we aired the first national episode on September 8, 1986, we already felt like a little family.

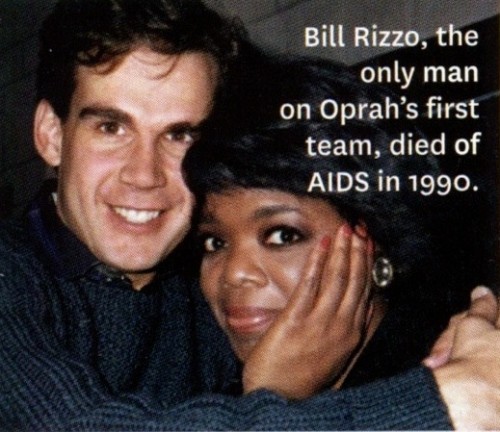

For two years after the premiere, we didn’t add a single person—we ran a national show with the same piddly staff! When you’re working 12, 15, and often 18 hours a day, your coworkers become more than just colleagues. They become friends. Even long after we made the move to Harpo Studios on North Carpenter Street and the staff grew, I felt a connection with that original group.

There’s no question about one thing: I’ve always had the best team in television. The producers who worked alongside me—elbow to elbow, and often around the clock—set the original gold standard.

—Oprah

“THE PERFECT PLACE TO BEGIN”

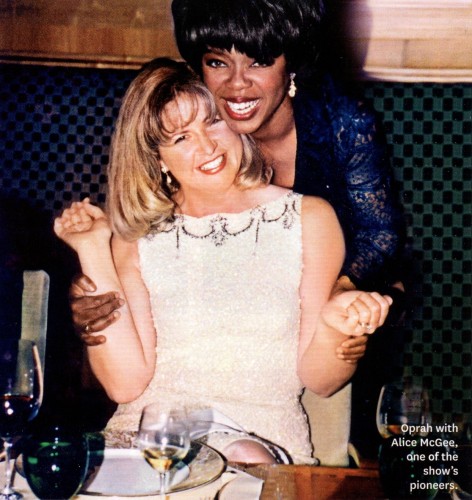

Alice McGee: Two weeks before the launch as Oprah traveled the country on publicity tours, she got field reports from us: Had we booked a big celebrity? No—and every day, another no would roll in!

Oprah: We tried every celebrity on the planet, but nobody paid me a bit of attention. They were like, “Who are you? Ophre? Okra?” We ended up going with a topic that had nothing to do with celebrities—”How to Marry the Man or Woman of Your Choice”—and that was the perfect place to begin. Because for 25 years, the show was about ordinary people who, like me, wanted to lead better lives. The premiere topic didn’t matter as much as setting the show’s intention.

Mary Kay Clinton: The night before the first show, Oprah had a green leather dress delivered to my apartment. The note said, “This is for our first big day,” and I was like, Oh my gosh. For the premiere, my job was to warm up the audience. In that dress, I felt like a million bucks.

Alice: After the first episode, we toasted each other with Champagne. Weirdly enough, the first show wasn’t that important to us—the first week was. People might tune in the first day, what about the second or fifth? We wanted to be consistently good.

Mary Kay: After the premiere, we went to Grant Park for a party—there was a huge tent with a band. But after a while, we were counting the minutes till it was over, because we had a live show the next morning.

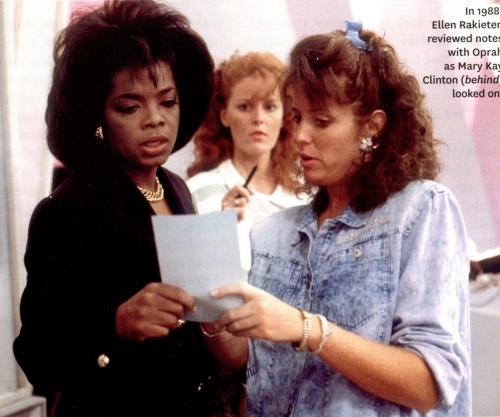

Ellen Rakieten: When we got the ratings for that first week, we did a happy dance. We even beat Donahue? Holy moly! Letters started pouring in. It was like, “Oh my gosh—people are actually watching?!”

Oprah: Any idea, any topic, any experience you wanted to have, you could have. It was thrilling. You could invite anybody in the world to come on. It didn’t mean they’d come, but many of them actually did.

Ellen: If we were interested in a topic, we felt our viewers would be interested. If one of us went through a breakup, for instance, we’d do a show about getting over a broken heart. Or if we were feeling fat, we’d produce a show on dressing skinnier. We had no plan, no infrastructure, no focus groups. I once gave Oprah a pair of Karen Neuberger pajamas. She said, “We should put these on the show!” I said, “Let’s do all your favorite things.” And that’s how it went: We sat in a room and made it all up.

Dianne Atkinson Hudson: We always broadcast live back then—and we each had a show to produce every four days. We rounded up guests by any means necessary—like by running plugs at the end of the program: “Are you a woman who’s stuck in an abusive relationship? Call the Oprah show.” People would call! They might say, “I want to be in that audience.” You’d say, “Why? Is this happening to you?” “No, it’s happening to my cousin.” “Where’s your cousin?” “She lives a couple blocks from her.” “Well maybe I should talk to her.” And if that cousin actually showed up as a guest, we knew we’d have resources to offer her—like an expert or a women’s shelter.

Alice: In those days, ordinary people didn’t appear on TV much. What was there for them to gain? We didn’t pay guests. All we had to offer them sometimes was a limo ride and lox and bagels for breakfast. So we had to reach into the deepest part of ourselves to explain why they should be on the show. You had to come from a place of truth.

Ellen: The number of people in our audience was often so pitiful that we’d have to go out on State Street at 6:30 a.m. and lure people in: “Free doughnuts and coffee!” To book guests, we’d go to a local bar the night before and announce, “We’re doing a show called ‘Single and Looking.’ ” Or we’d go to East Bank Club and put up flyers that read, “If you want to lose weight, call us.”

Lesia Minor: If were talking about sex, or if we had a celebrity like Eddie Murphy, it was a good pull for audience members. We might have Mel Gibson—who smoked on the set!—or Sylvester Stallone. We’d say, “Don’t you want to see Stallone this morning?”

Mary Kay: For every show, we wrote up cue cards—they’re like poster boards cut in half. Teleprompters had been invented, but they probably weren’t in our budget. On a day when I was producing a show, Dianne would hand me her script and say, “Do my cue cards.” We all did every job.

Alice: It was a riot backstage. Oprah once interviewed an animal psychic who brought out an alligator, and when Oprah came backstage afterward, the producer who booked that show was hiding in the closet. Oprah joked, “I want to shoot myself—but before I do that, I want to shoot you for putting me through this!”

Oprah: For ten years, I stayed after the show to greet every single audience member. Unbelievable. Then one morning, I couldn’t do it because I had a gynecologist appointment. On my way back to the office, I thought, I haven’t had this much energy in months—so that’s how the handshaking ended.

“WE WERE LIKE A SORORITY”

Alice: We all knew each other’s business. I’d say, “Ellen, I have a blind date with this doctor,” and she’d say, “Wear this.” She was like Rachel Zoe. Oprah would get involved—hard not to in such tight quarters!

Ellen: On Friday nights, we’d go into Oprah’s office and put on her makeup and jewelry. I’d say, “Oprah, can I wear those Wendy Gell earnings?” We were like a sorority.

Mary Kay: Oprah’s office had an open-door policy at all times. If we had worked all night, we would ask to borrow a shirt. And when someone was doing Oprah’s makeup for the show, we were right there with her. She’d say, “You’re not wearing any lipstick. Try this on to brighten up your face!”

Lesia: We’d try to outdo each other for parties, and especially for Oprah’s birthday. One time a producer gave Oprah a sheep to put on her farm in Indiana! It was hilarious.

Dianne: Oprah once walked into the office saying, “It’s Dianne Day!” She goes, “I’m so proud of you for quitting smoking.” She gave me an amazing leather suit. Another time, she gave us a trip to anywhere in the world. Even when we traveled, we’d say, “Let’s meet for dinner in Paris!” When you work together as much as we did—nights, weekends, holidays—you become great friends.

Oprah: We ate like hogs! I was the one who got lunch. “Should we go with Taco Bell?” I’d ask everyone, “or should we do Burger King?” I liked Burger King because it was only a block away. About 4 o’clock, I went out for Mrs. Fields cookies. Then in the evening, we’d all go out drinking on Rush Street.

Lesia: We always had Garrett Popcorn—the Chicago Mix, cheese and caramel. Another restaurant we loved was Soul By the Pound, which was two doors away. Smothered chicken, mac and cheese, grits, catfish on Fridays, and peach cobbler. Divine.

Mary Kay: I was the only one with a car—a Mazda RX-7—and we’d pile in and go to breakfast at Tempo Café. People would come up and say, “Oprah, I saw the show this morning! I could relate!”

“THE SHOW CHANGED ME”

Mary Kay: In 1987, I produced the show in Forsyth Country, Georgia—which had been virtually all white for 75 years. That experience helped me to understand how insidious racism can be. I was deeply affected by it.

Alice: I was the “lighten up” producer: I thrived on fun shows, like “Does Your Husband Notice You?” These women could have a frog on their heads, and the husbands wouldn’t see it! I’m also proud that we did radical TV: Oprah proposed themes like “the year of the child” or abuse or alcoholism.

Lesia: Oprah talked to juvenile sex offenders in season three. I found that show powerful because it showed how being molested had affected these children. They’d become offenders. The message for me was that you never know what’s going on in someone’s life. So many children don’t have a voice.

Dianne: In 1988, I worked on the National Coming Out Day show. It was one of the most challenging and rewarding experiences because it was an effort to encourage gay people to stand up. Now we’re discussing if gay people should marry—but in the 80’s, it was a crucial decision for them to come out. I felt proud to participate in that show.

Mary Kay: As a child, I was sexually abused by an uncle—and when we were local, Oprah shared her childhood experience with me. I said, “We should do a show.” I presented the idea to a WLS producer, and she said, “That’s a taboo subject. It won’t fly”—but Oprah said, “We’re definitely doing it.” She fought for it. Her ability to say, “You’re not to blame, you’re not alone” opened a huge door for her with viewers. And as I produced these kinds of shows and interviewed hundreds of survivors, that became a catharsis for me.

Oprah: Years after the premiere, I told Maya Angelou that opening a school in South Africa would be my greatest legacy—and she corrected me. “Your legacy will be the woman who decided to leave an abusive relationship,” she said, “or the mother who finally went back to school.” Putting that energy into the world for 25 years is what makes me most proud. And it’s an incredible tribute to the team who worked with such passion to pass on that spirit to viewers.